Saudi Arabia is one of Europe, Middle East and Africa’s (EMEA) top emerging markets, but it is on an unsustainable growth path that threatens long-term prosperity. In addressing this problem through economic diversification, the government will increasingly push multi-national corporations (MNC) to localize their presence or risk being shut out of the market. Success for MNCs requires that they demonstrate a willingness to add value to the Saudi economy by tightening relationships with local partners, hiring more Saudi nationals, and considering capital investments.

Saudi Arabia’s urgency for finding sustainable growth

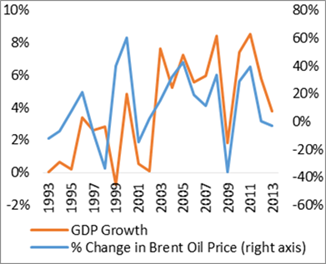

Saudi Arabia is seeking to support long-term prospects by addressing major economic vulnerabilities: an oil dependence and demographic challenges. What is often overlooked in analysis of Saudi Arabia’s oil dependence (accounts for 90% of government revenue) is how much the dynamic impacts growth. Between 1993 and 2013, the Saudi economy expanded by an average of 4.9% YOY in years that Brent crude prices increased, but only 1.8% YOY in years when prices decreased.

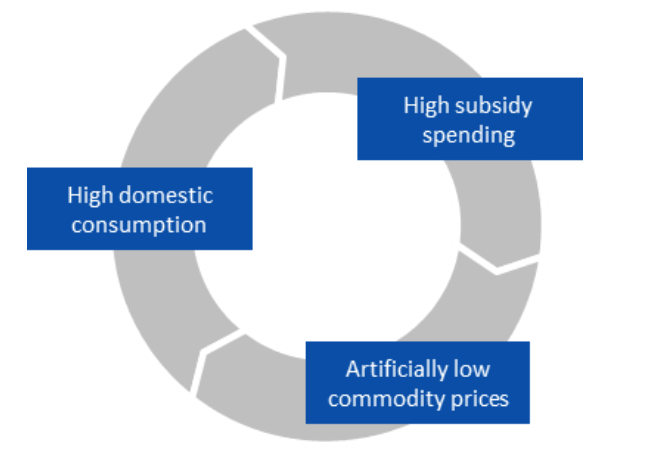

Furthermore, two-thirds of the Saudi population is under 30 years old and the youth unemployment rate is at least 30%. Demographic realities put pressure on the government, which must ensure enough jobs are created to keep up with 100,000 graduates entering the job market per year. However, a skills mismatch makes it hard to increase employment, especially in the private sector which is composed of nearly 90% expatriate workers. During the next decade, public spending will be increasingly tied up in recurrent expenditures, such as food and fuel subsidies, to provide for the country’s rapidly growing population.

Rising subsidy spending creates a vicious cycle that threatens to crowd out spending on priority sectors

Localization should be a basis of your Saudi strategy

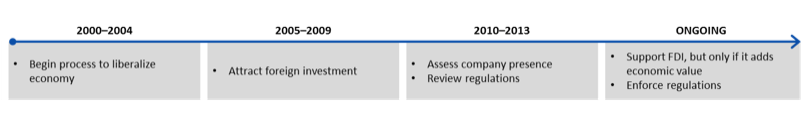

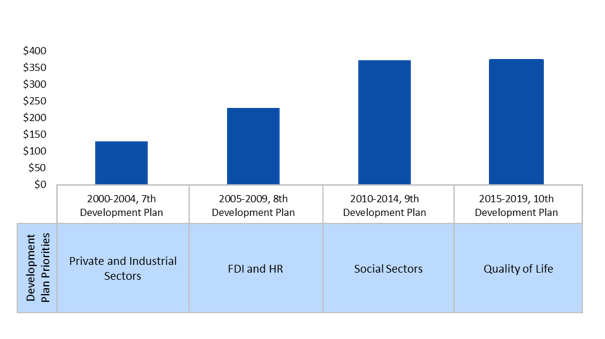

The Saudi government is enacting several policies, including economic diversification and Saudization, in order to promote sustainable growth. The good news is that by localizing their presence, MNCs can entrench their Saudi business to take advantage of opportunities and overcome obstacles associated with these policies. A local presence is particularly important for companies that want to sell into new customer segments, such as quality-of-life sectors (e-government, public transit, sports stadiums), and maintain a competitive edge in priority sectors (education, healthcare, housing).

Saudi Arabia’s recently announced 10th Development Plan lays out a blue print for significant spending

There are several challenges that require a local presence in order to be addressed. The government is becoming more selective regarding which foreign investors it allows to support diversification plans, though this is not always stated as an official policy. As a result, MNCs without a local presence are at a competitive disadvantage in critical areas of business, such as the bidding process for public tenders. In addition, an on-the-ground presence is the best way to ensure alignment with government priorities and understand the evolving role of the Saudi investment agency (SAGIA).

Three ways that MNCs can demonstrate a long-term commitment to Saudi Arabia

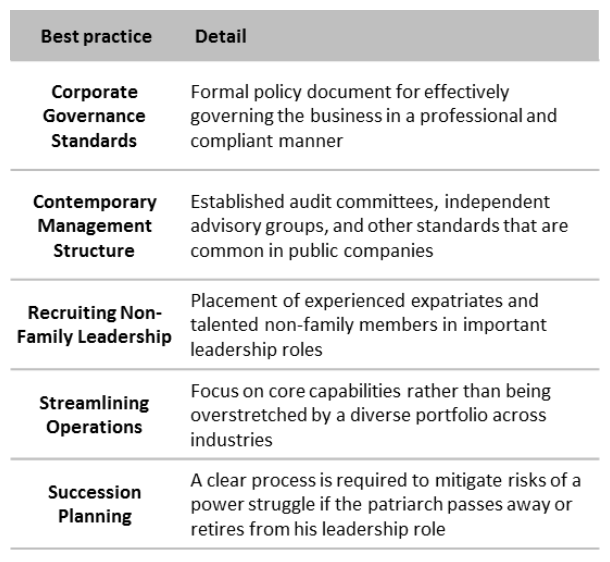

1. Offer to transfer knowledge to local partners that will help in their most pressing areas of need, such as instituting international corporate governance standards

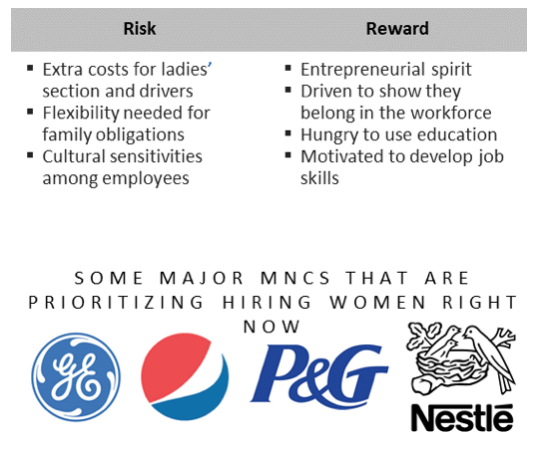

2. Consider hiring and developing more Saudi women, which aligns with one of King Abdullah’s top policy priorities and is a worthwhile risk

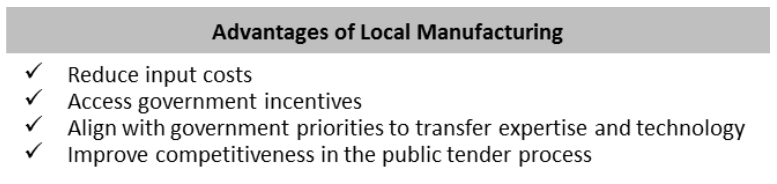

3. Look into setting up local manufacturing facilities to expand your reach in the Saudi market

In Saudi Arabia, foreign MNCs are faced with two simple options: be proactive and stay ahead of inevitable change or remain complacent and fall behind competition. The days of counting on high profits from your Saudi business without contributing to the local economy are over. Don’t fail to the see the writing on the wall.

***

Matthew Spivack is Frontier Strategy Group‘s head of research for the Middle East and North Africa. Prior to Frontier Strategy Group, Matthew worked for the National Democratic Institute on programs involving local government officials and journalists in Gulf Cooperation Council countries as well as anti-corruption initiatives, parliament, and political parties in Yemen. He also spent two years as a paralegal at the U.S. Department of Justice where he was the Victim Witness Coordinator for the Enron Task Force and worked on the largest FCPA case in U.S. history. Matthew has a master’s degree in Middle East Studies and Conflict and Conflict Resolution from George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs.